The Kaznacheyev Experiments

Dr. Vladimir “Vlail” Kaznacheyev (1924 - 2014) was the Director of the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine in Novosibirsk in Southern Russia. For 20 some years he directed groundbreaking and highly unusual experiments with twin cell cultures that everyone you know needs to be aware of...

These experiments are CRUCIAL to understanding disease and healing on a more fundamental basis than is presently grasped by proponents of orthodox medical science and the Warfare Model of health (i.e. those who still cling to “Contagion”).

The Kaznacheyev experiments (over 20,000 apparently) in the Soviet Union proved conclusively that virtually any cellular disease or death pattern can be transmitted electromagnetically, and induced in target cells absorbing the radiation

Here's How:

In the experiments, two sealed containers were placed side by side, with a thin optical window separating them. The two containers were completely environmentally shielded except for the optical coupling.

A tissue was separated into two identical samples, and one sample placed in each of the two halves of the apparatus. The cells in one sample (on one side of the glass) were then subjected to a deleterious agent - a selected virus [this begs the question and should read “virus,” as there is no legitimate test for a “virus” (including PCR) and the cytopathic effect can be obtained without a sample from a sick person! - Brendan], bacterial infection [“infection”], chemical poison, nuclear radiation, deadly ultraviolet radiation, etc.

This led to disease and death of the exposed/infected cell culture sample. If the thin optical window was made of ordinary window glass, the uninfected cells on the other side of the window were undamaged and remained healthy. This of course was as expected in the orthodox medical view.

However, if the thin optical window was made of quartz, a most unexpected thing happened. Some time (usually about 12 hours) after the disease appeared in the infected sample, the same features of disease appeared in the uninfected sample. This startling "infection by optical coupling" occurred in a substantial percentage of the tests (70 to 80 percent).

From an orthodox medical view, these results were unexpected and unheard of. Further, if the originally uninfected cells were in optical contact with the infected cells for 18-20 hours or so, and then were correspondingly exposed (optically coupled) to another uninfected cell sample, symptoms of the infection appeared in this third sample an appreciable portion of the time (20 to 30 percent).

Guided by A.G. Gurvitsch’s [also Gurwitch] work [early 1920s] that showed that cells give off mitogenetic radiation (photons) that can affect other cells, the Kaznacheyev team sought an answer by looking for photons given off by the infected culture sample as its cells died. They found that the cells in the infected culture gave off photons in the near ultraviolet when they died.

The normal window glass was opaque to these near-UV photons and absorbed them. In that case, the uninfected culture on the other side of the glass was not exposed to radiation by the UV "death" photons from the dying cells, and they remained serenely healthy.

However, the quartz window was transparent to the UV "death photons". When the quartz window was installed, the UV "death photons" passed through it and were absorbed in the uninfected culture on the other side of the window. Most of the time, the uninfected culture which absorbed "death photons" sickened and died with the same disease symptoms.

The Kaznacheyev experiments proved conclusively that cellular death and disease patterns can be transmitted and induced electromagnetically.1

We are faced with the electromagnetic/INFORMATIONAL transmission of “disease” with NO physical contact.

This rigorous research completely undermines Germ Theory which is a strictly materialistic (biochemical) paradigm—and breathtakingly outdated.

Not to harp, but Dr Stefan Lanka—who IS (or was) a virologist—has almost singlehandedly demolished the conceptual foundations of virology as a “science,” and actually demonstrated experimentally that the cherished “cytopathic effect,” that virologists have long used to justify the ASSUMPTION of the presence of a “virus” (with no proof!), is merely an experimental artefact which can be obtained WITHOUT adding fluids or cells from a sick person into the cell culture.

Back to Kaznacheyev’s revelations now.

As the late, great Tom Bearden—who had high-level government clearance and also happened to be a genius—explained,

The Kaznacheyev experiments showed that the dying cells from the infected culture emitted photons in the near UV that contained artificial (structured) potentials. The virtual-state, patterned-substructures in this photon flux directly represented the cellular disease pattern caused by the original cell's specific infection.

In other words, as the infected cells died, they emitted "death photons" which contained the template pattern of their death condition. When these "death photons" are absorbed into uninfected cells, their deterministic substructures gradually diffuse into the cell's bio-potentials. Gradually the biopotentials of the new cells are "charged up" with the integrated pattern of the disease.2 (emphasis added)

Further research by Golantsev et al. (1993) found that a mammary explant of lactating mice stimulated with some secretion-regulative hormones such as oxytocin, acetylcholine, epinephrine and norepinephrine can induce protein secretion in the other mammary explant of the mice even when separated by quartz glass.3 (emphasis added)

This has obvious health implications, and from this we can see how a relatively minor source of pain or discomfort could potentially irradiate nearby regions with the disturbed wave patterns and cause pain to spread.

More importantly, given humanity’s recent wayward trajectory under psyop 2020, this extensive research allows us to put a completely “new” spin on the idea of “infection.”

We are being forced to acknowledge that one does not need a physical mechanism such as a “virus” to communicate dis-ease or dysregulation from one organism to another.

(Note: I’m not saying that certain “opportunists” such as certain parasites or fungi don’t exist, by the way, that’s a whole other discussion which has to happen in the light of pleomorphism!)

In truth, the dynamics of “contagion” are far more subtle—in point of fact, it is all about information transmission, little more.

Even then, just because information is transmitted, doesn’t mean it needs to be enacted or adopted as one’s OWN biological program. 😉

Your worst enemy is actually BELIEF in contagion and the fear that typically follows.

Steiner explained decades ago that “viruses” are just cellular components (debris) ejected from cells undergoing detoxification.

As I have explained elsewhere and elsewhen, the reason a whole family gets “sick” together is usually because they are biologically entrained with one another, in a state of relatively high bio-informational harmony. (And they usually share many of the same environmental influences.)

The reason the cleaner who only visits a few hours a week remains magically “immune” is because she/he isn’t there long enough for her electromagnetic organism to synchronise with the family and manufacture a similar set of “disease” (healing) symptoms.

She/he is already resonating with a different biorhythm, so to speak (that of their own family).

The nanny, on the other hand, who spends 40 hours a week there and is more en rapport, might experience a sniffle and recover quickly. (I’ve actually seen this scenario play out!)

The photons (light) we exchange between us are considered to BE pure information, and biologically speaking, we are indeed “beings of (biophotonic) light,” communicating with each other in ways that are subtle but still measurable.

Wijk stated in a 2001 paper on bio-photons regarding cancer that,

As soon as the integration of a new cell into the population by cell division does not result in an increasing coherence of the system, the information for cancerous growth will arise. Consequently, the model of a coherent biophoton field, providing the basic communication of the cells in an organism, might help to understand cancer growth in terms of rather fundamental properties of a coherent field.4

What supports incoherent biofields?

Stress. Fear. Physical injury. Poisons.

We don’t need to invoke Contagion theology.

We could also infer logically that the opposite effects to those mentioned by Wijk can be achieved through photonic radiation or perhaps other forms of biological radiation; namely, energetic healing.

For example, using Therapeutic Touch healers against controls, Dr. John Zimmerman observed that the magnetic field increased remarkably during healing sessions. This experiment demonstrated that these biomagnetic pulsations from the hands of the healer are in the same frequency range as brain waves and they naturally sweep back and forth through a full range of therapeutic frequencies, stimulating healing in any part of the body.5

Other compelling research was done by Dr Valerie Hunt (Infinite Mind) back in the ‘80s measuring the electrical fields of people in close proximity to one another.

She measured (actually measured, not believed or assumed!) and proved that the electrical information of one person could become “contagious” to the other person, and thus, the recipient would take on a similar electrical pattern. This would happen when healers completed a healing session—the recipient’s field changed to match the healer’s, and at this point the healer intuited it was time to end the session.

Importantly, not all people underwent this type of exchange of information and yielded to sympathetic resonance. Some people's fields simply didn't change.6

You could consider that "immunity" in a "contagion" context.

Further Soviet investigation into cellular information transfer revealed that a uniform pattern, code, or rhythm of radiation was emitted by normal cells.

This pattern was disturbed when cellular damage occurred, becoming quite irregular, but, as noted, these patterns were transmitted from experimental to control preparations only when the cells or organs were cultured in quartz which allowed the passage of the so-called ‘death photons’. This caused the Soviets at the time to conclude that UV radiation mediated cellular information transfer.

The researchers subsequently correlated given irregularities of emission with specific diseases and since began attempting to develop techniques for diagnosis and therapy by monitoring and altering cellular radiation codes.7

This was already beginning as far back as the 1970s.

What can they do now? 🤔

From a 1975 DIA report we learn:

Czech research in parapsychology (psychotronics) had also yielded evidence that [electromagnetic radiation] was the vehicle of biological energy transfer from man to man and between man and animal. In experiments conducted between 1948 and 1968 at the Okres Institute of Public Health, Kutna Hora, Czechoslovakia, Dr. Jiri Bradna demonstrated contactless transfer (myotransfer) of stimuli between frog neuromuscular preparations.

Bradna placed identical preparations side by side; stimulation of one preparation with electric pulses at frequencies between 10 and 30 pulses per second caused contraction and a recorded electromyographic response in the other. In other experiments, stimulation of muscle preparations influenced the oscillations of a pendulum and increased the muscle tension of a human subject.8

Bradna’s evidence indicated “that energy in the very high frequency range mediated the stimulus transmission. He also demonstrated that myotransfer could be blocked with ferrous metal filters and aluminium, could be deformed with magnets, ferrites and other conductors, could be reflected and transmitted over wave guides, and shielded with grids.”9

It is known that when you apply a chemical called ethidium bromide to samples of DNA, the chemical squeezes itself into the middle of the base pairs of the double helix and causes it to unwind, releasing photons (light).

Following a student’s suggestion for a new experiment, Dr Fritz A. Popp (1928 - 2018), a German researcher in biophysics, discovered that the more of this chemical he used, the more the DNA unwound, and more significantly, the stronger the light emissions were.

He also found that DNA was capable of sending out a large range of frequencies and that some frequencies seemed linked to certain functions. If DNA were storing this light, it would naturally emit more light once it was unwound. These and other studies demonstrated to Popp that one of the most essential stores of light and sources of biophoton emissions was DNA. DNA must be like the master tuning fork in the body. It would strike a particular frequency and certain other molecules would follow.10

In bio-photon emissions, Popp believed he had found an answer to the question of morphogenesis as well as cell coordination and communication. Popp showed in his experiments that these weak light emissions were sufficient to orchestrate the body. They had to be low intensity because these communications were occurring on a quantum level, and higher intensities would be felt only in the world of the large.11

Popp’s conclusions support those of Gariaev et al., who contended that quantum non-local communication is at the foundation of the body’s functioning.

Herbert Frolich was one of the first to introduce the idea that some sort of collective vibration was responsible for getting proteins to cooperate with each other and carry out instructions of DNA and cellular proteins. He even predicted that certain frequencies just beneath the membranes of the cell could be generated by these proteins.

Wave communication was supposedly the means by which the smaller activities of proteins, the work of amino acids, for instance, would be carried out and a good way to synchronize activities between proteins and the system as a whole.12

In his own studies, Frolich had shown that once energy reaches a certain threshold, molecules begin to vibrate in unison, until they reach a certain level of coherence (resonance). The moment molecules reach this state of coherence, they take on certain qualities of quantum mechanics, including nonlocality.13

So it seems that the Bose-Einstein condensate finds a macro-level biological equivalent in living wetware systems (us!), in this sense.

Meanwhile,

Fritz Popp's Nobel prize-winning research establishes that every cell in the body receives, stores and emits coherent light in the form of biophotons. In tandem with biophonons (acoustic energy), biophotons maintain electromagnetic frequency patterns in all living organisms. In the words of Stephen Lindsteadt, this matrix that is produced and sustained by frequency oscillations "provides the energetic switch boarding behind every cellular function, including DNA/RNA messengering.

Cell membranes scan and convert signals into electromagnetic events as proteins in the cell's bi-layer change shape to vibrations of specific resonant frequencies." Emphasizing that every "biochemical reaction is preceded by an electromagnetic signal..."14

According to the pioneering Gariaev (who used lasers to informationally turn frogs into salamanders and vice versa), “the importance of quantum non-locality existence for a genome is hard to overestimate.15

The quantum non-locality of genetic information is fundamental to the work of Gariaev, Webb et al., and others in explaining the formation, maintenance and organisation of our physical bodies.

In other words, cutting edge research into DNA (assuming for the sake of argument that it really exists as a quasi-stable structure) basically requires the reality of hyperspatial (nonlocal) connections between DNA strands and cells throughout the body.

This instantaneous communication facilitates the incredible holistic functioning of the human body..

Curiously, Fritz Popp's research in biophotons describes the dying process of cells as virtually identical to that of stars. Just before dying, cells transform into "supernovas" as the light they emit increases in intensity a thousand times before being suddenly extinguished.16

As above, so below, in our holofractal universe. Sagan did tell us we’re “made of star stuff,” after all.

They Tried and Failed

As detailed previously, if you bother to look, you’ll see that trying to transmit supposed “viral infections” from one person to another is not easy. In fact, no one has ever really succeeded in scientifically demonstrating isolated cellular debris (or misidentified exosomes) called a “virus” does ANYTHING harmful in the body.

Actually, some disgusting experiments on “transmission” were done many years ago—things that would probably be considered "unethical” by today’s standards.

Doctors attempted via various unpleasant means to infect healthy volunteers with the “flu” from men who were deathly ill.

Bodily fluids were shared. Breath was inhaled. Eye drops of sputum were implemented. Blood transfusions.

But they failed. Over. And Over. And over.

No one got sick.

The physicalist approach yielded ZERO “contagion” (and this is far from an isolated instance).

Or watch the video HERE

Being briefly in the presence of VERY sick men—even sharing bodily fluids!—was not enough to electromagnetically contaminate the healthy volunteers and induce dis-ease symptoms—in ANY of them.

As Karl Muller states in an excellent blog, it comes down to electromagnetic information sharing, though I would remind you that “exposure” does not automatically mean “illness”, as the above experiment shows:

…it’s actually very clear in Carmel Mothersill’s research. She told us in an email how some fish were exposed to a non-lethal dose of a toxin, and were then put in a tank with other fish, “swim buddies”. Then they were all given a massive lethal dose of this toxin (I could never do experiments like this).

Control fish that had no previous exposure were 100% all killed outright. Of the pre-exposed ones, about 45–50% survived. But of the “swim buddies”, 50% also survived. So they benefited just by being in vicinity of other fish that had some pre-exposure.

Diseased cells induce disease states in their neighbouring cells. Diseased individuals do the same to healthy individuals. And vice versa: the presence of healthy individuals can reverse disease in their neighbours. And it’s frikkin biophotons that are mediating these effects.

Viral “infections” are not in the least caused by physical bits of virus being transmitted. Ill people make the people around them ill literally through their electromagnetic aura.17 (emphasis added)

In other words, “contagion” operates purely electromagnetically and informationally—AND psychosomatically, as I emphasised in my recent Anarchapulco talk (available only to members of The Truthiversity), where I explained in detail how the convid-19 psyop exploits both mass formation and the nocebo effect in a way you won’t find anywhere else.

The role of the psyche is VASTLY underestimated in all this, as I’ve been saying since the early days of what I like to call cooties-19 (or clownvid-19). 🤡

We know from many realms of research (see, for instance, Dr Sarno’s tension myositis syndrome, the work of Dr Harvey Bigelsen and sons, or Dr Hamer’s German New Medicine) that almost any symptom or illness can be explained WITHOUT needing to postulate “viruses.”

Most (but not all) of it, in truth, we unconsciously create through stress with our very own minds—but many are unwilling to grapple with this possibility and fully flesh out the perhaps disturbing ramifications (a subject of great interest to me).

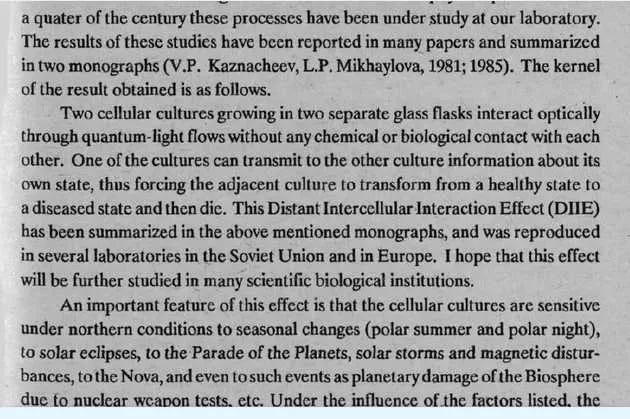

And just to more fully tease out the significance of environmental influences on biology as we wrap things up, I present these words from Kaznacheyev’s book Cosmic Consciousness (primarily the bottom paragraph):

As he says, the cellular cultures (read: our biology!) were sensitive to seasonal changes, solar eclipses, planetary movements, solar storms, magnetic disturbances, biospheric damage, and so on.

Look at what you’re being distracted from by focusing on “viruses” and contagion fear-porn (including all the “gain of fraudtion” nonsense).

Look where the belief in contagion and “viruses” got us these past few years (while mortality rates stayed normal until the jabs were rolled out!).

Look what mainline medicine has done to public health over the last 200 years whilst operating from the Warfare Paradigm that assumes the existence of these tiny bogeymen and then sets about trying to poison us into “immunity.” 😂

Are we learning to ask the right questions yet? 🤔

Qui bono?